Many lives are lost across USA because emergency services fail

By Robert Davis, USA TODAY 07/28/2003

WASHINGTON — Help came too late for Julia Rusinek. The 21-year-old Yale sociology student, an accomplished runner, collapsed on a busy street corner in the nation's capital on a summer evening in 1999 after working out at a nearby gym.

Rusinek had more than a fighting chance to live: She was healthy except for a hidden condition that caused a sudden electrical short circuit in her heart. Her heart needed a zap — within six minutes — from a common medical device known as a defibrillator. Bystanders saw her fall, rushed to help and immediately called 911.

But Rusinek's life ticked away on the corner where she fell. Twelve minutes passed before an ambulance crew connected a defibrillator to her chest. Like thousands of others every year in cities across the country, Rusinek lost any chance she had to survive because of an emergency medical system that consistently fails to save as many lives as it should.

In post-9/11 America, where war and fears of terrorist attacks have brought the need for effective emergency response into sharp focus, a USA TODAY investigation finds that emergency medical systems in most of the nation's 50 largest cities are fragmented, inconsistent and slow.

People die needlessly because some cities fail to make basic, often inexpensive changes in the way they deploy ambulances, paramedics and fire trucks. In other cities, where the changes have been made, people in virtually identical circumstances are saved. Those sharp differences surfaced in the 18-month investigation, which included a survey of city medical directors, analyses of dispatch and response data; interviews with fire and ambulance crews and on-site visits and ride — along with "first responders."

Rusinek's case illustrates the failures of the system: She died of sudden cardiac arrest, a condition that serves as one of the truest measures of an emergency medical system's effectiveness. Whether victims live or die depends primarily on how fast they get treatment. For years, the conventional wisdom was that help must come within 10 minutes. But new findings from the Mayo Clinic show that lives actually are saved or lost within six minutes.

The USA TODAY survey and data analysis show that, of the 250,000 Americans who die outside of hospitals from cardiac arrest each year, between 58,000 and 76,000 suffer from a treatable short circuit in the heart and therefore are highly "saveable." Yet nationwide, emergency medical systems save only a small fraction of saveable victims, and rates vary widely from city to city.

The analysis shows:

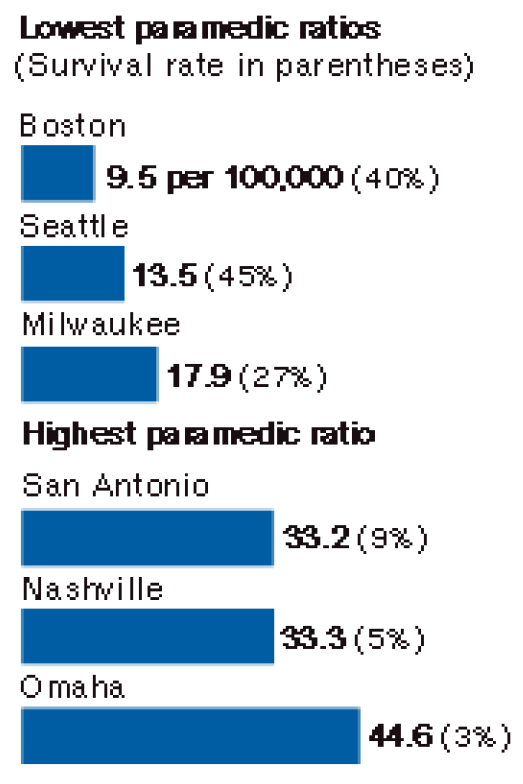

- Chance of surviving a dire medical emergency in the USA is a matter of geography. If you collapse from cardiac arrest in Seattle, a 911 call likely will bring instant advice and fast-moving firefighters and paramedics. Collapse in Washington, D.C., and — as one EMS official suggests — someone better call a cab for you. Seattle saves 45% of saveable victims like Rusinek; Washington, D.C., has no idea how many victims like Rusinek it saves. The city estimates it saves 4% of cardiac arrests, but inconsistent record-keeping makes it impossible for Washington to account accurately for its most saveable victims.

- In the nation's 50 largest cities, about 9,000 people collapse each year from cardiac arrest caused by a short circuit in the heart. Only an estimated 6% to 10%, or as few as 540, are rescued. If every major city increased its save rate to 20%, as a number of cities have done, a total of 1,800 lives could be saved every year.

Like Rusinek, those who could have been saved are often young and vibrant: corporate executives who die at work, students who drop dead in school gymnasiums, commuters who never come home from their jobs.

At the same time, Rusinek's case was unusual. At least three people witnessed her collapse and the emergency response. Her family sought answers from rescuers, and details of her death were reported in the media. Most victims are hidden from public view by sealed medical records and a health care system that routinely tells families their loved ones "died instantly" and "we did everything we could."

What is not said — and what families often do not know to ask — is precisely how, and how quickly, emergency services responded to the call for help.

Over the next three days, USA TODAY will delve into three major reasons that emergency services in most U.S. cities are saving so few people in life-or-death situations:

- Many cities' emergency services are undermined by their culture. Infighting and turf wars between fire departments and ambulance services cause deadly delays.

- Most cities don't measure their performance effectively, if at all. They don't know how many lives they're losing, so they can't determine ways to increase survival rates.

- Many cities lack the strong leadership needed to improve emergency medical services. Leadership — by the mayor, the city council and community health officials — can make a dramatic difference. Boston, for example, more than doubled its survival rate over 10 years under the direction of a strong mayor who demanded change and enlisted city officials, businesses and many residents in the drive to save lives.

Tackling turf wars

Of these three problems, turf wars between paramedics and firefighters — the focus of today's articles — arguably are the most challenging.

The conflict has developed over time as rescuers' roles have changed. Call for an ambulance today in a big city, and the first rescuers to arrive are often firefighters. Most cities have turned their firefighting teams into rescue squads as medical emergencies have become more common than fires.

"The logic is obvious," says J. David Badgett, an assistant chief with the Los Angeles Fire Department. "Geographically, fire stations are close. There are a lot of us in the fire department. We're an emergency service agency."

Every major city has more fire engines than ambulances, and while both a fire engine and an ambulance are dispatched to the scenes of most serious medical calls, fire engines often are closer and able to get there first.

Today's average fire department answers twice as many calls for medical emergencies as for fires. The job of dealing with the sick has slowly nudged aside the task of dousing flames.

The shift has been met with resistance in many fire departments, USA TODAY found. Many firefighters said they were unhappy because they signed on to fight fires, not to tend to sick people. Beyond that, fighting fires is sharply different from delivering emergency care.

"The typical firefighter is a very linear person," Badgett says. "They see a problem, they defeat the problem, they leave a winner. On a fire you do that. Emergency medicine isn't like that."

It takes time and experience for firefighters to feel comfortable using some medical equipment without paramedics backing them up. So even though firefighters usually are trained to use defibrillators — the portable devices that shock a dying heart back to life — some admitted in interviews that they were hesitant at first to do it in a real crisis by themselves.

Jeremy Gruber, a Montgomery County (Md.) Fire Rescue captain, paramedic and Washington D.C.-area defibrillator trainer, says delivering advanced medical care is often most difficult for the veteran firefighters. "We have people who have been on the job for 30 years, and they are used to doing it one way and they have never really evolved with the technology and the changes," he says.

Fire departments that want to deliver medical care, he says, should "hire people who are already medically trained so you know they have an interest in that. You're not going to be able to force-feed somebody who doesn't want to be there."

Failure in Washington, D.C.

The changing roles have caused resentment in many big-city fire houses, and resentment can affect performance. Washington, D.C., exemplifies the problem.

First aid is part of a Washington firefighter's job. A fire engine responds with an ambulance on serious medical calls. But the crews don't always work well together.

Over 18 months, a reporter visited Washington crews on the front lines dozens of times, sometimes scheduled, sometimes unannounced. During those visits, emergency workers were more likely to be at each other's throats than watching each other's backs.

Ambulance crews made it clear they view firefighters as lazy; firefighters view ambulance crews as undisciplined. Every day in Washington, firefighters and the paramedics who back their ambulances into the same fire stations are likely to be quarreling over everything from where they park and what they eat to whose job it is to care for the sick and injured.

In 2001, using stopwatches, city officials found that Washington firefighters don't respond as quickly to medical calls as they should. Their finding prompted the city to buy global positioning equipment so officials could track the movement of rescue vehicles.

USA TODAY reviewed more than 85,000 emergency calls to examine those delays more closely. The analysis of turnout time — the time it takes for firefighters to run to their rig and roll out the door toward an emergency — shows that Washington firefighters' median response time was faster to a dumpster fire than to a report of a cardiac arrest.

The fire crew responding to a report of a structure fire got rolling in 82 seconds, despite having to don protective boots, pants, coats and breathing apparatus. In response to a report of a cardiac arrest, which requires no special preparation, the crew took 124 seconds to reach the rig.

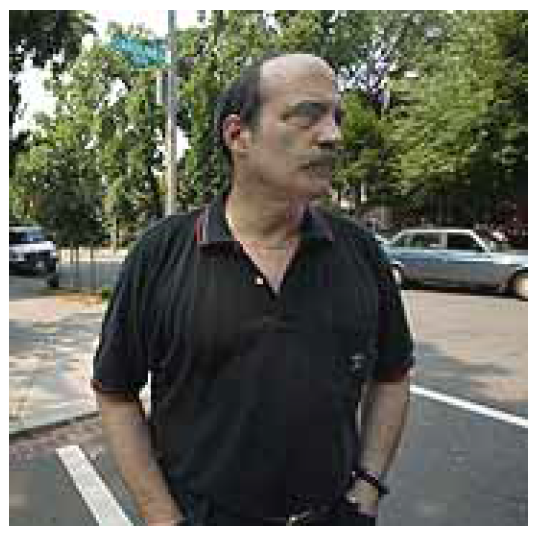

Kenny Lyons, who heads Washington's paramedic union, tells his loved ones not to waste time dialing 911 if they face a dire medical emergency. "If they can find someone to drive them to a hospital, drive them. If they can somehow catch a cab, go," he says. The poor performance of the system, he says, "is haunting to the providers, and it should be chilling to the community."

Washington's culture problems are not unusual. Most cities refused to answer USA TODAY's question comparing response times on fires and emergency medical calls, but a few cities, including San Francisco, Mesa, Ariz., and Wichita, said their firefighters also are slower to respond to medical emergencies than to fires.

Medical directors, doctors hired by the cities to supervise emergency medical care, are often aware of these delays, but many told USA TODAY in the survey and interviews that they are viewed as outsiders by firefighters. The directors can make suggestions to improve care, but the fire chiefs have the final say about how money will be spent and how resources will be deployed.

In Los Angeles, fire department commanders and a powerful firefighters union view fire suppression as the main focus of the department, with medical services "a very distant second," says medical director Marc Eckstein.

He says many obstacles, including a "lack of attention to emergency medical systems issues, overwhelming priority in terms of training, and budget for fire-suppression activities instead," stand in the way of better performance. Still, he says, "our department is much further along in merging the two cultures than most."

In St. Louis, tension between fire suppression and emergency medical crews results in fights over funds and misunderstandings about the other side's jobs and concerns, says medical director Mark Levine. Within this embattled system, efforts to monitor performance have been "poor but improving," he says.

Of the 28 medical directors who answered USA TODAY's question about what forces in their systems affect performance and patient outcomes, 16 cited fire department culture or unions as key.

Fernando Daniels, Washington, D.C.'s medical director, was one of them. "The traditional thinking was bad: 'All we want to do is put fires out,'." says Daniels, who is in his third year in the job. He has begun an ambitious plan that includes mass CPR training, getting defibrillators into more buildings and measuring the system's performance accurately.

But like the would-be reformers before him, Daniels has struggled to see his fixes take hold in a culture resistant to change. "To make the system work, you've got to get those barriers down," he says.

The firefighters union says the barriers go up in cities when fire and ambulance services are merged poorly. Firefighters now provide the vast majority of "pre-hospital" emergency medical service in the country, says Harold Schaitberger, president of the International Association of Fire Fighters. "And they do it with professionalism, commitment and esprit de corps that is unrivaled by any other public safety sector."

Where ambulance services and fire departments are merged "on a systematic basis with strong leadership, ample training and education, and effective response protocols," the result is very successful, Schaitberger says. "What creates confusion are those cities, like Washington, D.C., that have EMS (ambulance service) under the fire department umbrella, but in actuality EMS is still a separate service with a separate command structure, separate training regimens, separate pay and benefit programs, and more transient employees.

"In these cases, firefighters often feel no affinity with EMS. They wince when EMS is criticized by the public and the media because it reflects on the fire department, yet they have no control and little participation on the EMS side of operations."

Washington fire chief Adrian Thompson, who was named to the post by the mayor last November, says he is taking steps to address this problem. Over the next month, he says, the fire department will undergo a major change of structure. All ambulance crew members will have to apply to be firefighters to keep their jobs, a move aimed at establishing a uniform standard for all employees of the fire department. And in the future, he promises there will be a paramedic firefighter on all 33 of the city's fire engines.

"People don't realize that with firefighters and EMS workers, one group seems to thumb their nose at the other group," Thompson says. "We hope that this will bring some unity to the department."

Lyons, head of the paramedics union, has his doubts. Quality emergency care, he says, requires "full-time dedicated paramedics and emergency medical technicians that are committed — not forced — to provide patient care."

"While many will argue that dual-role cross-trained personnel will provide a bigger bang for your buck, what it will provide is more firefighters and few paramedics," he says. "This attitude has forced many paramedics out of the profession and discouraged many others from pursuing EMS as a career."

Deadly delay

From his 16th Street apartment window in Washington, D.C., Jonathan Agronsky says, he saw Julia Rusinek on the ground on the evening of July 15, 1999. He rushed to the firehouse less than a block from where she fell.

The firefighters there said a fire engine from another station farther away had been dispatched and was on the way. The ambulance crew was going off duty.

"I was so mad I couldn't see straight," Agronsky recalls now. "I could have throttled those guys."

He and a fire official agree that only after another man ran into the station saying the woman down on the street corner was turning blue did Truck 9 roll. Lt. John Desautels, the officer in charge on Truck 9 that day, says he and his crew were following protocol designed to send smaller fire engines, not the long ladder trucks, to medical emergencies. "The initial call was a woman down," Desautels says. "We get 100 of those a day," and most are not life-threatening cases.

When it became clear the situation was more critical, he says, they drove to the woman's side. But they did not use their defibrillator, Desautels says, because his men reported that the woman had a pulse. Instead, they called for Ambulance 1, still in the station.

Then the firefighters watched — along with anxious bystanders — as the ambulance rolled down the fire station driveway, then turned in the opposite direction and drove away, Desautels says. The crowd yelled at the Truck 9 firefighters, who called the dispatcher to tell the ambulance to turn around.

Desautels says Rusinek's heartbeat disappeared just as the ambulance arrived and that the firefighters performed CPR, but they still did not use their defibrillator. By the time the ambulance reached Rusinek, she had been down for 12 minutes. The ambulance crew shocked her repeatedly, but she was declared dead at a hospital a mile from where she fell.

Rusinek's family visited the fire station to try to learn what happened. "Many people there were totally unconcerned," her mother, Roza, says. But "one fireman there dared to look us in the eye, and he was crying."

That fireman was Desautels, who has been honored three times for heroics at the scene of fires, including for daring, lifesaving rescues. "I had to explain how sorry I was," he says.

But the mother, who immigrated from Poland, is still critical of the ambulance crew that initially refused to attend to her daughter because the shift was ending. "I can't imagine how good an evening that person had to make up for our tragedy," she says.

Agronsky, an author who went on to write about the woman's death in Washington's alternative City Paper, is still angry. "I could have put her on my back and walked her to the hospital, and she would have had a better chance of surviving," he says.

Rusinek's death should have been a wake-up call for Washington's emergency medical system. It was an opportunity to study the flaws in the system and make improvements. It's rare when a victim collapses so close to help, goes so long without having a defibrillator applied and still is a candidate for a shock more than 10 minutes after collapse. It is even more rare when such an episode becomes public knowledge.

But her death didn't change things much. The city's average response time for fire engines going to medical emergencies was slower in 2001, the year studied by USA TODAY, than in 1999. Ambulance response times improved only slightly in that interval.

And problems remain. Last December, for example, a paramedic was dispatched to a report of a cardiac arrest at 6:01 p.m., but his shift ended at 6, so he drove back to his firehouse to go off duty, according to news reports. Firefighters performed CPR on the victim for 25 minutes until the new paramedic crew climbed into the rig and drove to the scene from the firehouse about five miles away.

Unlike Rusinek, the victim had chronic health problems and was not a candidate for defibrillation. He wasn't in the category of the most saveable, so his death was not shocking. But the response — which made local headlines — was.

Success in Seattle

In 2001, Seattle saved 45% of victims like Rusinek — those who are seen going down and who suffer from a treatable short circuit in the heart. And unlike Washington, D.C., Seattle is able to provide a detailed accounting of its victims.

One of the biggest factors contributing to Seattle's success is its culture. There, the medicine delivered in the streets comes from firefighters and fire department paramedics who have very different jobs but work on the same team. Each has a well-defined role to play in the patient's care, with firefighters reaching victims first and performing basic care until paramedics arrive to administer advanced cardiac life support.

Paramedics grade the firefighters' care on critical trauma calls. They fill out a "blue sheet" that details what the less-trained emergency medical technicians on the fire department team have accomplished by the time the paramedics arrive.

That accountability pushes first responders to deliver rapid treatment and have the patient ready for transport. It gives critical feedback on how they performed and what they can do better next time. It helps the paramedics spot the firefighters with a knack for emergency medicine as they look for new recruits. And the paramedics are scrutinized on every run by their medical director, Michael Copass. Copass reads every run report, and the paramedics know they will be called to task for any error. They say they feel him looking over their shoulders as they make care decisions.

Seattle has led the nation's big cities in emergency medicine research and provided the model that medical directors have followed in other cities, including Washington.

Washington, D.C., Mayor Anthony Williams says his administration is rebuilding city agencies that long have been in disrepair, including the fire department. "We're improving," he says. "We're just starting from way, way behind in so many areas. We're moving our way up, and I think you're going to see that improve."

His medical director hopes that changes come quickly.

"These disparities shouldn't exist," says Daniels, who vows that Washington one day will have an emergency medical system as good as Seattle's. "Folks need more scrutiny. We are here to save lives."

Contributing: Rati Bishnoi, Tracey Wong Briggs, Jacqueline Chong, Anthony DeBarros, Neal Engledow, Mary Grote, Erin Kirk, Jim Norman, Paul Overberg, Emma Schwartz, In-Sung Yoo